“Welcome to everybody’s neighborhood,” said Mayor Rusty Paul at September’s groundbreaking at City Springs, as two dozen residents heeded his call to bring soil from their neighborhoods to mingle at the site.

That $220 million redevelopment fulfills a major promise the city made in its first decade: to create a new downtown. But, as the mayor’s ceremony of symbolic unity suggests, Sandy Springs is also still in the process of inventing itself.

“Sandy Springs, 10 years into its existence, still struggles with our identity,” said Paul in a recent interview. Creating a sense of place and community through redevelopment remains a priority that will define the city’s next decade, he said.

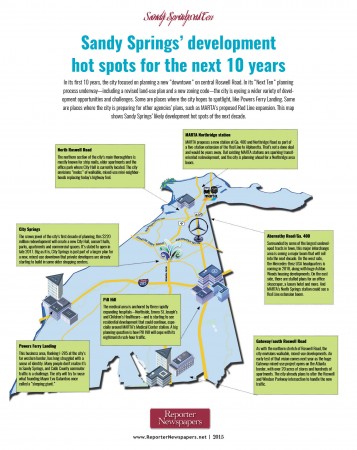

The city’s “Next Ten” planning process is tackling that challenge head-on. Continuing into next year, the process will set new standards for redevelopment, in part by looking closely at both popular areas and neglected corners of the city. Community leaders express optimism about the Next Ten— though with varying degrees of caution.

“I think that they’re probably going to do a very good job of figuring out which way people want us to go in the future,” said Trisha Thompson, president of the Sandy Springs Council of Neighborhoods.

“I’m eternally optimistic, but I’m definitely feeling, as an HOA president, very hesitant,” said Matt LaMarsh, president of the Mount Vernon Woods Homeowners Association, who lives in one of the hottest redevelopment spots at Ga. 400 and Abernathy Road.

Everyone agrees that traffic congestion is the city’s biggest challenge. A rebuild of the Ga. 400/I-285 interchange will be a defining project of the next decade, but it’s just part of possible solutions that may bring more local MARTA stations and transit-oriented development. Sandy Springs, a city founded on localism, likely will join in more regional planning, officials say.

“I see a crystal ball that looks very bright, very promising,” said Yvonne Williams, president and CEO of the Perimeter Center Improvement Districts, describing Sandy Springs as poised to seize opportunities and overcome challenges.

A SENSE OF PLACE

It drives the mayor crazy when locals use “Atlanta” rather than “Sandy Springs” in their street addresses, or when people think the King and Queen buildings are the city’s downtown.

“Part of [the future] is to create this larger sense of community…the sense of place like Marietta has, like Decatur has,” Paul said. City Springs is a massive attempt to do that by combining a new City Hall, performing arts center and parks with a mixed-use project. When it opens in 2017, it should anchor a more walkable downtown. And, Paul said, it will tie together some disparate Sandy Springs neighborhoods, like the southern end around Chastain Park or the panhandle that often identifies as Dunwoody.

“That’s a legacy project,” said City Manager John McDonough. “I think even five years from now, you’ll see a completely different landscape. I think [there will be] more focus on community, more interaction among people.”

But even as it builds that landmark project, the city is looking ahead to a different kind of place-making. Instead of rebuilding entire neighborhoods, the next phase is more about adding to them. Paul said he’d like to see the rest of Roswell Road lined with small, walkable clusters of shops and restaurants instead of shopping centers—“a little community meeting space, if you will.”

“We want to broaden the horizon of what a neighborhood is,” he said. “In the next 10 years, that’s kind of our vision.”

THE NEXT TEN

The Next Ten process is how Sandy Springs will put such visions on paper. Among the results will be a new Comprehensive Plan of land-use guidelines; a new, unified zoning and building code; and several “Small Area Plans” giving detailed visions of such areas as Roswell Road’s northern and southern reaches.

“The focus on the next 10 years is different from the first 10 years,” said McDonough. “The first 10 years focused on creating the delivery system” for city services, planning and infrastructure, he said. Now it’s about delivering the products, especially City Springs, but also the more refined input process of the Next Ten.

“We should have broad community support. If we don’t, we missed our mark,” McDonough said of the development that will follow the Next Ten guidelines. “In the end, it should be the community’s plan.” Thompson, the Council of Neighborhoods

president, said the Next Ten isn’t exactly grassroots planning, but does involve more public input than ever.

“I’m not sure it is building [a plan] on public input, but I truly believe this new crew [of planners], they are scouring every nook and corner of Sandy Springs they can think of to garner opinion,” she said. Thompson said the future of Sandy Springs lies in pushing for higher-quality development standards, and that the current mayor and City Council are more responsive to that, especially after the Glenridge Hall estate controversy earlier this year.

“They see the older homes coming down. They see trees coming down,” she said. All developers know how to build projects that contribute to a good quality of life, Thompson said, adding, “It’s just whether we can force them to do it in Sandy Springs and not bring their cheap end.”

LaMarsh isn’t as convinced that the city’s leaders are on the right track. He and wife Melissa are part of Sandy Springs’ post-cityhood generation, having moved here from Acworth four years ago to be closer to Atlanta and start a family in a “dynamic community.”

“We certainly got it,” LaMarsh said with a laugh. The land surrounding their neighborhood is now the site of two enormous and controversial housing plans by developer Ashton Woods. LaMarsh has been a leader in the debates, at one point threatening to sue, and more recently helping broker a key compromise. There’s no guarantee that city leaders will stick to the new development guidelines, LaMarsh said.

And he worries that most big parcels will be built out already with less thoughtful projects.

“My concern here is the damage has been done and it’s going to be hard for us to climb out of [existing projects],” he said. “My fear is we’ve moved a little too far, a little too fast.”

However, LaMarsh counts himself a fan of some pending projects, including City Springs.

“I think the future of the city is bright and we do have some good things coming down the pipe,” he said. “Hopefully we can continue to protect the neighborhoods that kind of made Sandy Springs, Sandy Springs.”

TRAFFIC AND TRANSIT

With all of the growth comes traffic, and solutions to it may reshape several parts of the city. The billion-dollar project to add lanes on Ga. 400/I-285 will start in about a year and wrap up in 2020. But potentially even more landscape-changing is MARTA’s proposed Red Line extension to Alpharetta. The Next Ten includes transit-oriented development studies around the existing North Springs station and a potential Northridge Road station.

“Long term, to absorb population growth…we need to have more efficient transportation, and the only way we’re going to do it is mass transit,” said Mayor Paul. “Unless you have transit…we are going to drown in traffic, and we’re going to kill the goose that lays the golden egg and destroy our quality of life.”

While it may not feel like it at rush hour, “We’re ahead of the curve” on long-term traffic solutions, said the PCIDs’ Williams. The Perimeter Center’s future includes shuttle systems, more sidewalks and multi-use trails, and more east-west connection roads. Other possibilities include a bus rapid-transit route along the Perimeter to Cobb County, she said.

“We’re going to see a very walkable district,” said Williams. In fact, the future may be largely about getting Sandy Springs out of its car. Walkability is key to the sort of place-making the mayor envisions at both City Springs and the mini-neighborhoods of Roswell Road.

“If we can do that over the next 10 years,” Paul said, “we’ll be a long way toward making Sandy Springs the most enviable community of [metro] Atlanta.”

This article comes as part of a special section in the Nov. 27 issue. Read it digitally: