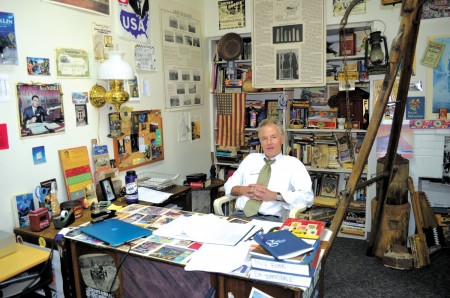

Stuff from American history clutters Allen Barksdale’s classroom. He’s got scores of items big and small, from a gunslinger on a comic book cover to a mining pan from the Dahlonega gold rush, from a huge scale that once weighed bales of cotton to a Ben Franklin action figure.

“I see it as like an American culture headquarters,” he said.

Jill Stedman’s history classroom appears a bit more formal in decoration. Portraits of past presidents line the walls, framed with colored backgrounds that indicate their political parties.

Each high school history teacher’s approach to the subject matter can follow a slightly different track. Teachers admit that.

“Personal preference by the teacher is always going to be part of the class,” Barksdale said in his cluttered classroom at The Galloway School. “I don’t think that’s a bad thing. I see my work as an educator isn’t to indoctrinate or tell people think one way or another, but to get them excited about learning.”

But when it comes to the tangled history of the United States, deciding what and who should be included in classroom lessons have become part of a very public battle in some parts of the country, including Georgia.

The latest fuss has broken out over the Advanced Placement U.S. History course, known as APUSH, which is put together by the New Jersey-based College Board, a not-for-profit company that also devises the SAT and other national tests. In 2015, 17,829 Georgia students took the end-of-course AP test that can be used to win college credit for students, according to the College Board.

In Colorado, parents and school board members drew national attention when they publicly criticized revisions to what schools were told to teach in their AP history classes. Some Georgia school officials joined the criticism and the Georgia Senate in March voted 38-17 to adopt a resolution saying “the APUSH framework reflects a seemingly biased view of American history that overemphasizes negative aspects of our nation’s history while omitting or minimizing many positive aspects.”

The Senate resolution said the course framework did not include adequate discussion of “the country’s Founding Fathers, the principles of the Declaration of Independence, the religious influences on our nation’s history and many other critical topics…”

Sen. Fran Millar (R-Dunwoody), one of the sponsors of the resolution, said he felt the revised AP U.S. program “tilted too far in one direction.” “I felt [it] was too revisionist,” he said.

Sen. Judson Hill (R-Marietta), another sponsor, said he saw at his dinner table what he felt were “substantial changes” taking the course in a direction he did not approve. Two of his children took the AP U.S. history course in successive years, he said, and during family discussions “my daughter was asking me unusual questions about American history and my son had not asked those questions the year before.”

He took what he called “a deep dive” on the new course and didn’t like what he found. “In my view, America is not the cause of all the problems in the world,” he said.

Faced with criticisms like that, the College Board announced it would revise its APUSH courses this year. “Every statement in the 2015 edition has been examined with great care based on the historical record and the principled feedback the College Board received,” the organization said in a statement. “The result is a clearer and more balanced approach to the teaching of American history that remains faithful to the requirements that colleges and universities set for academic credit.”

Critics say they’re looking over revisions this year to see how they work out.

But history teachers, including current and past AP U.S. History teachers, say that complaints about the coursework give teachers too little credit for what they teach. The story of history, they say, is told in the classroom, not the paperwork.

“What’s really most important is the intent and philosophy of the teacher,” Barksdale said.

At Pace Academy, Tim Hornor, who taught AP U.S. History for 11 years, thinks critics of the AP U.S. History course curriculum were concerned about a framework for the course that would be used by teachers only as a guideline.

“The [College] Board is not telling you what you can and cannot teach,” Hornor said. “It is not as if they would say, ‘Please don’t teach [President and Declaration of Independence author Thomas] Jefferson. No teacher of U.S. history would leave out George Washington. The framework is a framework, not a guidebook.”

At Holy Spirit Preparatory School, a Catholic school, Stedman also argues an engaged teacher is an important part of determining what students are taught, and, importantly, what they learn.

“If you have a competent teacher, that’s all going to work itself out,” said Stedman, in her ninth year of teaching APUSH classes. “It’s all about teacher quality. It’s not the curriculum.”

Stedman said that her class actually became more rigorous. Her chief worry about the APUSH course last year came from changes to the end-of-the-year test used to determine how well students understand the subject. But her students, she said, performed well on the test.

She thinks complaints about the AP course dovetailed with complaints about the Common Core standards, which were devised as a way to reach national standards in English and math, and have drawn widespread criticism. The standards have been adopted in 42 states, including Georgia.

Riverwood International Charter School AP World History teacher Daniel Gribble also thinks worries about Common Core spilled over into criticisms to the changes to AP U.S. History. “It is the perception that Common Core is the top-down model and that is trying to take away local control,” he said.

But, he said, the changes give classroom teachers more control. “The new curriculum actually gives you more freedom to teach,” he said.

Barksdale, who has taught at Galloway since 1997, said he can’t imagine a U.S. history course that doesn’t include significant events or moments such as Washington’s Farewell Address or historic personalities such as Andrew Jackson. “I would be teaching that regardless of whether it’s on the [AP] test,” he said. “I think any teacher would be doing that.”

Still, the overarching point of studying U.S. history is to understand the complexities and changes in the country.

“The real thing I would want them to get is just a real interest in their country and knowing how things got to be the way they are,” Barksdale said. “Having that [knowledge] would help them to be good citizens in every sense of the word.”