The historic “Battle of Atlanta” Cyclorama painting is back as part of a major new permanent exhibit at the Atlanta History Center that opens Feb. 22.

A Feb. 21 preview of showed the 130-year-old painting, which depicts the key Civil War battle in gigantic, circular format, is back in an eye-popping restoration. Unlike its display at its former home in Grant Park, the painting is hung under tension with a slight curve that creates an optical illusion of depth of the battlefield’s landscape.

The painting was moved in 2017 from Grant Park to the History Center at 130 West Paces Ferry Road in Buckhead. After two years of work, it is on display in a custom-designed wing that includes an enormous circular chamber containing the painting and a 15-foot-high platform from which to view it. The painting is about 50 feet high and 370 feet around.

After more than two years of painstaking restoration work, the Cyclorama painting is now part of a larger exhibit called “The Big Picture.” As the name implies, it gives a larger context of Atlanta’s history and the myths and realities of the Civil War. Other prominent Atlanta artifacts on display in the wing include the legendary 1856 locomotive the “Texas,” which was once involved in the chase of another locomotive stolen by Union troops; the Zero Mile Post that long marked the original city center; and the Solomon Luckie lamppost, named for an African American barber who was killed during the Battle of Atlanta’s shelling in 1864.

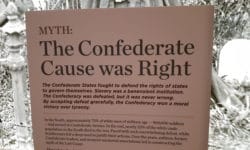

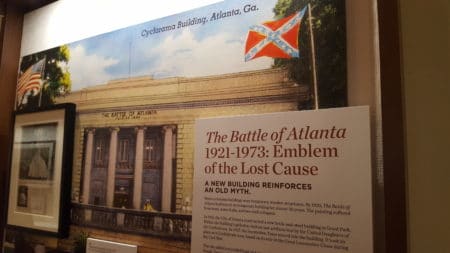

The exhibit addresses several Civil War myths, especially the “Lost Cause,” a heroic vision of the Confederacy that ignores slavery as a key motivator of the war. The Cyclorama painting is itself an artifact that became part of local Lost Cause mythology.

An entertainment fad of the late 1800s, Cycloramas were huge, circular paintings of dramatic scenes intended to give the viewer an immersive experience—“the virtual reality of its time,” as Gordon Jones, the History Center’s senior military historian and curator, previous put it.

The “Battle of Atlanta” painting was created by artists in Minnesota in 1886 as a dramatic tribute to Union Gen. William Sherman’s key victory in seizing and destroying Georgia’s capital. Among its dramatic licenses was including a soaring eagle – “Old Abe,” a mascot of a Wisconsin Union regiment that did not fight in the battle and would not have let the bird fly if it had, Jones says.

The painting toured several states in temporary displays before ending up in Atlanta, where it was altered to suit pro-Confederacy tastes. One famous change – later reversed — was repainting Confederate prisoners of war to transform them into fleeing Yankee troops. After the city constructed a permanent building in Grant Park to house the painting in 1921, it became a local icon of Lost Cause myths.

Only 17 Cyclorama paintings survive worldwide, museum officials say, and “The Battle of Atlanta” might have joined the others in rotting away if it were not for two African American mayors. Maynard Jackson, the city’s first black mayor, ordered a restoration that was completed in 1982, saying it was important to save a tribute to a key battle in a war that helped to free his ancestors. In 2011, Mayor Kasim Reed gathered a group to find a new and safe home for the painting as talk began of selling its Grant Park building.

The History Center won the rights to host it by raising nearly $36 million for the restoration, new building and long-term conservation, starting with a $10 million gift from residents Lloyd and Mary Ann Whitaker.

The complex symbolism that now attaches to the Cyclorama painting is addressed in an introductory movie that is projected onto the painting itself as an orientation. The movie features actors depicting various points of views: the artists who made and altered the painting; Union and Confederate veterans seeing themselves in its battle; and women and African Americans who were left out of the picture, though not out of the real war.

For tickets and more information, see the Atlanta History Center website at atlantahistorycenter.com.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly said “The Texas” was stolen by Union troops; it was involved in the pursuit of another locomotive that had been stolen.

Photos by John Ruch.