Fresh from debuting a major exhibit reinterpreting the Cyclorama painting of a Civil War battle, the Atlanta History Center is hard at work on a similar “reinvention” of the display about another city cultural touchstone: the 1996 Summer Olympics.

The original Olympics exhibit, which opened 10 years after the Games, was largely celebratory and packed with artifacts and memorabilia. The new version – set to open in July 2020 to coincide with the next Summer Olympics in Tokyo – will take a wider view. In part, curators say, that means highlighting lasting legacies like Centennial Olympic Park and the city’s global reputation. It also means giving space to previously underplayed protests about lack of transparency and equity, and a time when the Olympics world is shaken by corruption scandals and criticism of financial and social impacts.

“As we’re looking 20 years down [the road], it’s a different story,” says Sarah Dylla, the curator of the new Olympics exhibit. The concept will be less about the “day-to-day or medal count” and more about “social and cultural change,” she said.

“The historical perspective is different,” said Dan Rooney, the History Center’s exhibitions director and the curator of the original Olympics exhibit. “We recognize as time passes, perspectives change.”

The former Olympics exhibit in the History Center’s 130 West Paces Ferry Road museum, featuring a wide range of artifacts and memorabilia ringing an artificial running track, is already gone, disassembled partly to make way for the new Cyclorama wing. For now, the space serves as an oversized corridor between the gift shop and the Cyclorama. Its walls are sparsely hung with a note about the forthcoming exhibit and some images of Atlanta Olympics venues, and even that took some careful thought, the curators say, as they didn’t want to commit to a particular narrative or angle early on.

But as the work continues and the 2020 deadline looms, the theme is boiling down to one of the favored buzzwords of the International Olympics Committee, the Switzerland-based nonprofit that controls and runs the Games.

“In the Olympic world, they talk a lot about the word ‘legacy,’” said Dylla, referring to the IOC’s jargon for buildings and programs that are supposed to provide lasting improvements to a host city. In the broadest terms, she said, the exhibit will look at “what it means to be an Olympic city,” a status that puts Atlanta in a “small group of Olympic cities around the world looking in terms of legacy and impact.”

Original exhibit

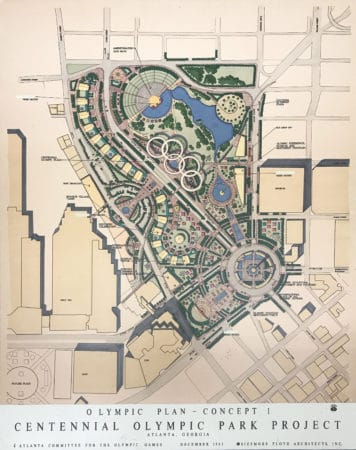

Right after the excitement of hosting the 1996 Games, that legacy looked easier to process. The focus was on the triumph of Atlanta winning what was by any account an improbable bid for the historic 100th edition of the modern Summer Olympics, led by Dunwoody real estate lawyer Billy Payne. Downtown Atlanta was rapidly transformed by such major projects as the park and a stadium that later became Ted Turner Field and is now Georgia State’s football field.

One intended legacy of the Games was a tribute to the Olympics itself – a museum planned for Centennial Olympic Park. A financial study determined the museum was not feasible, Rooney said, so in 1996, the committee of business leaders that organized the Olympics donated more than 6,000 objects and records to the History Center instead. The History Center purchased the items in 2001 and opened the Olympics exhibit in 2006 as part of a 10th anniversary celebration.

Rooney said his concept for the exhibit was marking the 100th anniversary of the modern Summer Olympics, putting it in historical context, and showing how the Games addressed “gender, race and war and world politics.” As viewers moved around the track-like path, they saw ancient artifacts from the 1,000-year history of the Greek Olympics, displays about the modern Games, the 10-year life of Atlanta’s bid and hosting, and day-by-day events from the 1996 competitions.

“The exhibit was about times and hours and minutes and records being broken,” Rooney said.

One disturbing event the exhibit had to address was the infamous bombing of the park by a right-wing terrorist as part of a campaign against abortion and gay rights, followed by the misidentification of a heroic security guard as the culprit. That will be an even bigger challenge to tackle in the new exhibit, and Dylla says they’re looking at how other museums are dealing with such “difficult history” and making appropriate space for victims.

But, as Dylla and Rooney think about how to arrange a 2,600-square-foot exhibit space for 2020, that’s just one of many challenges. There’s no shortage of items in the vast collection, but anything going on display has to pass what Rooney calls the “so what?” test.

“I always believe that museums are about objects, but first they’re about ideas,” he said, explaining that the curators must figure out the key stories that will resonate with the public and choose objects that illustrate them.

Reinterpreting the Games

The sheer number of stories to tell about the Atlanta Olympics is daunting for an event that sprawled across metro Atlanta to such venues as rowing on Lake Lanier and horse events in Conyers – among places that the History Center may coordinate with, Rooney says, so the exhibit may “grow beyond four walls here.” And there was the international bidding process that included Atlanta defeating Athens, Greece, the historic home of the original ancient Olympics, in internal voting.

“Really, I’m struck by the breadth of connections the story has,” said Dylla. “You can see so many parallels to things happening in other Olympic cities and thing happening in world history in the 1990s.”

“[There’s] a big story of technology that’s one of our favorites right now,” added Dylla — the World Wide Web was new and the Atlanta Olympics was the first to have a website and online ticket sales. Looking back at that now-clunky tech could be fun, as is going through a collection of “a lot of funny-looking old pagers and cellphones.”

“You do not want to drop that cellphone on your foot,” joked Rooney about one of the brick-like models used by the Atlanta Games committee.

Some of the simplest legacies of the Games – like a widely acknowledged boost in civic pride – requires creativity in turning into a museum display.

“I think Atlanta is touted as overcoming an almost insurmountable quest, which is to win an IOC bid… And to a certain extent, I think it’s fair to say Atlanta does have this recurring persona of being able to rise to the occasion beyond all expectations,” says Rooney. But how can he show such an intangible emotion? A presentation of oral histories from people involved might be one element.

At the same time, the curators want to avoid truisms and clichés. Citing one of the favorites, Rooney said they need to “be careful saying, ‘Atlanta became more international because of the Olympics,’” when it really was among a “complicated series of causes” to demographic changes.

Then there are the aspects of the Atlanta Games that didn’t look so glorious to many people at the time and don’t tend to show up in museum exhibits or other commemorations. The mass displacement of residents from Summerhill and the Georgia Tech area, mostly lower-income and African American, for Olympic facilities drew protests at the time. Lavish gift-giving by bid committee members prefigured a major IOC bribery scandal a couple of years later. The city was sued over laws intended to drive homeless people away from Olympics venues and tourists. Some venues later became money-losers or were demolished.

And globally, the Olympics’ legacies of corruption, secret planning and white-elephant venues have caused a major reinterpretation of the Games themselves and new IOC promises of reform. The 2024 and 2028 Summer Olympics hosts were chosen in an unusual double-award desperation move as the IOC faced cities dropping out amid concerns over financial costs, budget secrecy and social impacts – and the winning cities, Paris and Los Angeles, both have protest movements that hope to force out the Games. Various Olympics officials are caught up in yet another round of bribery investigations. The U.S. Olympics Committee is mired in scandal over cover-ups of sexual abuse of hundreds of young athletes dating back to Atlanta’s Olympics era.

Part of the new exhibit, Dylla says, will be putting the Atlanta Olympics in the context of the “lack of participatory planning” that’s become a global issue, and the inclusion of “more different stories of resistance and dissenting voices.”

Rather than relying solely on the existing collection, Dylla is speaking with some of the residents involved in Atlanta Olympics protests, including from the anti-displacement activism. Another movement she’s studying is Olympics Out of Cobb, an LGBTQ protest that successfully got that county shut out of all Games venues and programs after its commission issued a resolution condemning gay people. “They made a bunch of cool schwag,” she adds.

The remake of the Olympics exhibit bears similarities to the History Center’s reinterpretation of the Civil War-themed Cyclorama painting: a public entertainment that became a lens through which Atlanta saw itself, and which the museum is now putting in a deeper context, along with puncturing some of its pernicious myths. It’s the last of the center’s permanent exhibits scheduled for a major makeover, but Rooney says the real point is how “permanent” never is.

“People talk about permanent museum exhibits, but we want to correct that,” says Rooney, explaining that long-term but subject to inevitable change is more accurate. As the History Center preps a new look at post-Olympics Atlanta, he says, “museums don’t have all the answers, and maybe there was a time museums presented themselves as being the authority, and maybe sometimes that was delivered without community dialogue and community participation.

“Communities need museums,” Rooney said, “but museums need the community as well.”